‘The Four Continents’ Chandelier

Jan Frans Allaert

by Frank Huyghens

The most beautiful room in the rococo city palace which the museum has called home since 1922 is the dining room on the ground floor. Here, you can see one of the masterpieces of the collection, i.e., the imposing wood-carved chandelier, that was designed and carved by the Ghent sculptor, Jan Frans Allaert (1703-1779) in 1770.

While it may look as if the chandelier has always been hanging from the ceiling of Hotel De Conick, this is definitely not the case. We have yet to find an 18th-century document that proves that Allaert designed the chandelier for this room, in addition to creating the interior and layout of the room. The first source that describes this room and attributes the whole interior to Allaert only dates from 1868, one hundred years after he created the design.

We do know for certain that the textile merchant, Ferdinand Joan De Coninck (1728-1791), and his newly-wed wife, Terese Scholt, moved into this stately townhouse in 1762. The interior of the dining room had been completed one year earlier. The scenes on the elm wood panelling refer to love in a relaxed, pastoral setting. The gods look down benevolently from the Olympus in the ceiling painting by the Ghent artist, Pieter Norbert Van Reysschoot (1738-1795).

In any event, the chandelier looks like it was designed for this room and is consistent with the life story of Ferdinand De Coninck. Its style is definitely suited to the room: the airy, flamboyant rococo resonates in the interior and in the chandelier. The chandelier’s dimensions also seem right for the room.

The central theme of the chandelier is the representation of the four continents, depicted here as four children sitting at the foot of a palm tree. This allegorical representation was often used in homes where the master of the house wanted to demonstrate that he was a man of the world. Ferdinand De Coninck’s family traded with the Northern Netherlands, Spain and the overseas territories. This dining room enabled him to show off his happy marriage and his prosperous business ventures to his guests.

Europe wears a helmet, with a plume and a king’s crown and carries a sword. The necklace of the Order of the Golden Fleece hangs from her neck. The child stands over a cannon, legs wide apart, and is flanked by an eagle with a globe. The eagle and the necklace are a reference to Joseph II, the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. The Austrian Habsburg family ruled the Southern Netherlands since 1713. Was Ferdinand De Cock demonstrating his allegiance to his ruler, hoping for social promotion? We know that he was knighted in 1782, twelve years after he designed the chandelier.

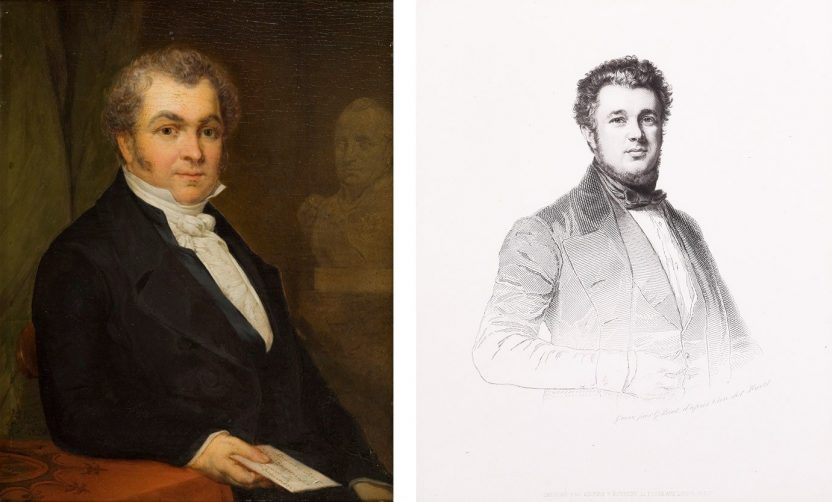

Portret Ferdinand De Coninck by Balthazar Beschey

America is represented here as a Native American Indian, wearing feathers on his head and carrying a bow in his hand. A ship sails in between the figures of Europa and America. Merchant ships were often associated with America. Ferdinand De Cock also made part of his fortune trading with the overseas territories. What is strange, however, is that Allaert designed a real warship with several cannons.

Asia is sitting astride a camel and is wearing a turban. A camel? A turban? Allaert clearly thought that Turkey symbolised the unexplored continent. Africa wears an elephant’s skull on his head, and a lion lies next to him. The horn of plenty refers to the endless slew of colonial goods that were imported from this continent. Strangely enough, Allaert chose to fill the cornucopia with corn ears. According to Cesare Ripa’s iconographic handbook “Iconologia”, this horn should contain ears of grain.

Allegorical representation of the continent of Africa from Iconologia by Cesare Ripa, edition 1603

The top of the chandelier is equally difficult to explain. A nest of eaglets is concealed by the foliage of the palm tree. An eagle hovers over the nest, with a dragon pup in its claws. Does the predator represent King Joseph II, who protected his subjects against the barbary of the Ottomans? In 1771, the king broke his alliance with the Ottoman empire. A tiny monkey is suspended from the bottom of the chandelier. Like “chinoiseries”, these so-called “singeries” were a fashionable, entertaining and exotic motif in the elegant rococo interiors.

Portrait of a young lady with monkey by Rosalba Carriera, ca. 1721

Whether it was designed for Hotel De Conick or not, this chandelier has had several owners. We know that Norbert d’Huyvetter of Ghent purchased it in 1852 at an auction of his father’s art collection, Joan Norbert, for 2,200 BEF. In 1925, the d’Huyvetter loaned the chandelier to the museum, where it was exhibited for quite some in the dining room. In 1961, it resurfaced in the shop of a Brussels antiques dealer. At the time, the museum took advantage of the opportunity to purchase the chandelier, even though several international bidders also expressed their interest. Since 1973, it is displayed in the dining room again.