A cosmopolitan chair for Philippe Wolfers' smoking room

Paul Hankar

by Marie Becuwe

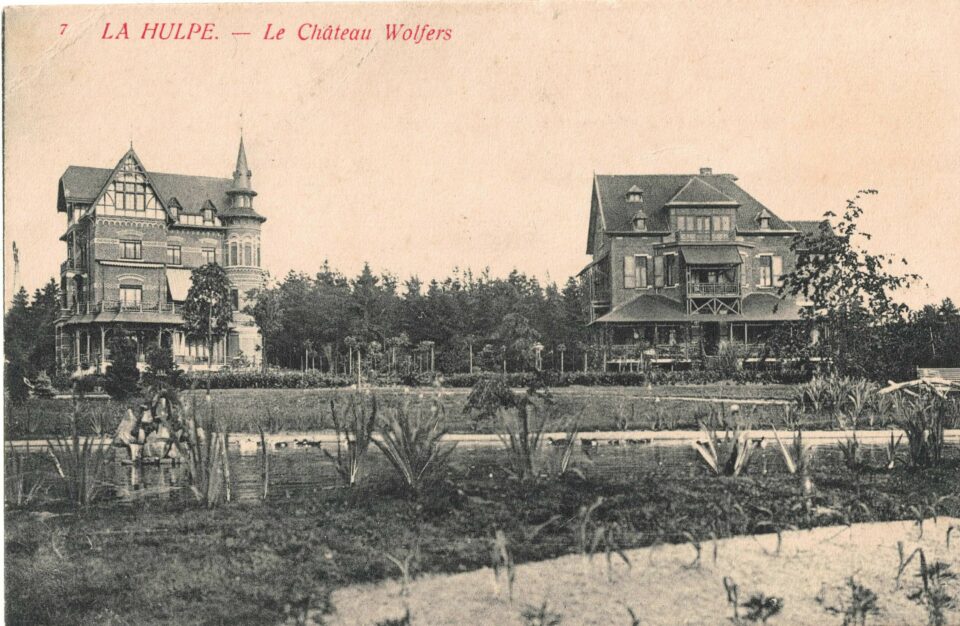

Towards the end of his life, the Brussels Art Nouveau architect Paul Hankar (1859-1901) designed a country house for his friend, the silversmith and artist Philippe Wolfers (1858-1929). In 1899, Philippe Wolfers purchased a plot of land in a new development in the hamlet of Maleizen on the border of Overijse and Terhulpen, together with his brother Max and his cousin Albert. Maleizen found favour with many rich inhabitants of Brussels because of the verdant surroundings and the easy connection with the capital. The Wolfers brothers and their cousin cemented their social status as owners of the flourishing silversmith company Wolfers Frères with the construction of a spacious country residence. Paul Hankar was tasked with designing the entire property of the Wolfers family, except for the villa of Max Wolfers. He created the villa Les Glycines (glycine is the French word for wisteria) and a separate design studio for Philippe Wolfers in addition to the villa Les Mimosas for Albert Wolfers.

Portret of Paul Hankar © Géruzet Frères

The villas of Max and Albert Wolfers © Théo Van den Heuvel, private collection

Villa Les Glycines of Philippe Wolfers © Philippe Wolfers Archive, King Baudouin Foundation

The entire concept had a distinctly oriental feel to it, which is typical of the artistic climate of that era. After Japan’s self-imposed isolation drew to a close in 1854 with the signing of international trade agreements, an obsession with all things Japanese swept Europe and America. Japanese art objects and prints found their way to Western consumers through galleries, art collections, magazines, and world fairs. For artists, Japonisme provided a welcome creative turn while the upper classes embraced this new trend with gusto. Art Nouveau was heavily influenced by Japanese art and its stylised design, craftsmanship and diverse range of materials, as is evidenced from the work of both Paul Hankar and Philippe Wolfers. The country residences of the Wolfers family also highlight how influences from Japan, China and the Middle East seamlessly merged with each other in the West. Hankar added a Japanese ornamental garden with a bridge over a water lily pond and an aviary with peacocks and rainbow pheasants to the park. The covered balconies and balustrades with their stylised motifs lent Philippe Wolfers’ cottage the appearance of a Chinese pavilion.

The design’s oriental inspiration culminated in the interior of the smoking room of Villa Les Glycines, for which Paul Hankar designed a unique set of furniture. Three identical chairs, a stool and a table from this room found their way to the collection of Design Museum Gent by way of Philippe’s son, Marcel Wolfers. Despite the prevailing idea that the smoking room had a Japanese aesthetic, the influence of traditional Chinese interiors, in which furniture played a central role, cannot be underestimated. In Japanese interiors, the few pieces of furniture were frequently incorporated in the architecture and concealed behind sliding doors, staircases, or trapdoors.

Portrait of Philippe Wolfers (Adriaenssens & Steel, De Wolfers dynastie, 2006).

Chair for the smoking room of Villa Les Glycines © Design Museum Gent, www.artinflanders.be, an initiative of meemoo, photo Cedric Verhelst

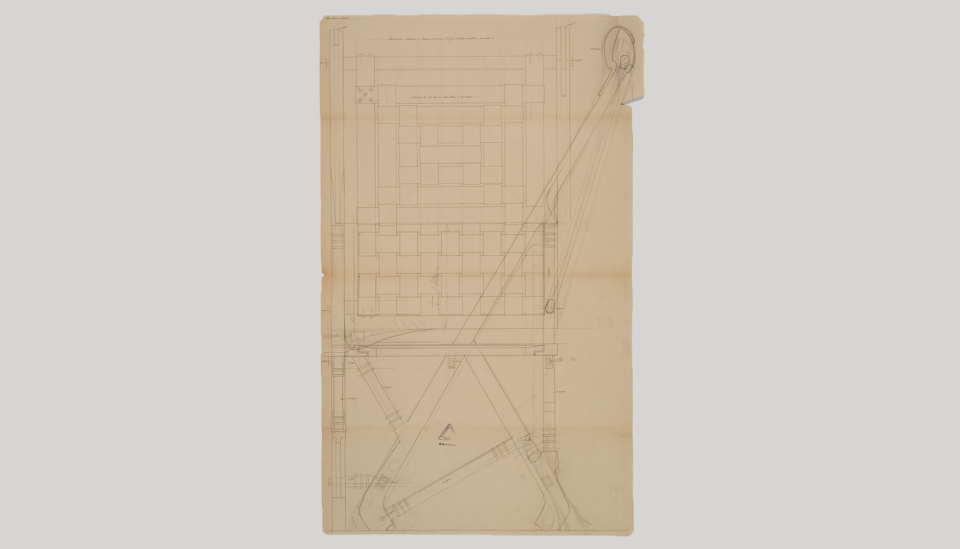

The chairs for the smoking room bear witness to Paul Hankar’s distinctive personal style. Unlike Victor Horta, whose style combined curves and curling lines with floral motifs, Hankar clearly preferred a simpler, more geometric approach. The chairs explicitly point to his interest in the Far East. The restrained, simple design with stylised ornaments, the woven leather and the combination of dark and light wood are typical oriental elements. At the formal level, the chair design bears similarities with traditional Chinese and Japanese folding chairs. That said, chairs were relatively uncommon in Japan, where people preferred to sit on the floor. Seating furniture, which found its way to Japan from China, mainly had a prestigious function in shrines or as a status symbol for the Japanese elite.

Stool for the smoking room of Villa Les Glycines © Design Museum Gent

It is easy to see why the chairs are associated with the Far East as elements of an oriental inspired smoking room. Hankar, however, may also have been inspired by Africa, where folding chairs were widely used in a colonial context, for his designs. Colonial powers, such as Great Britain and the Belgian King Leopold II, used folding chairs and other campaign furniture on their international expeditions. Their simple, functional shapes and the use of leather clearly overlap with the chairs for the smoking room. Besides colonial furniture, Paul Hankar may also have been inspired by African furniture. After all, he had had plenty of opportunity to study Congolese shapes and materials as the interior designer of the Congo section of the 1897 World Fair, which was dedicated to Leopold II’s Congo Free State. The furniture that Hankar created for the Palace of the Colonies in Tervuren was produced in Congolese materials and, in some instances, referred to domestic furniture types, such as the stool used by the Luba people of the Congo. Profiled wood joints and the use of mahogany and leather for this style congo are also characteristic of his later chair design for the smoking room.

Table for the smoking room of Villa Les Glycines © Design Museum Gent

Sketch of the chair (profile and cushion) © KMKG Art & History Museum Brussels, Paul Hankar Fund, dossier Cottage Wolfers Philippe Overijse

Paul Hankar combined these ‘exotic’ influences with elements from the neo-Flemish renaissance, the style of his teacher Hendrik Beyaert. The combination of tradition and innovation was a constant in Hankar’s furniture art. The influence of this neo-Flemish renaissance is especially evident in the chair design, in the use of leather and of the visible mortise and tenon joints. Hankar’s rational construction of the chair, with predominantly oblique lines, is also indebted to the rationalism of the French architect Eugène Viollet-Le-Duc. As such, the smoking room chair, with its multiple sources of inspiration, is a remarkably cosmopolitan object.

Sources

- Paul Hankar Fund, dossier Cottage Wolfers Philippe Overijse, Brussels: KMKG Art & History Museum Brussels.

- Sandro Bocola (ed.), African Seats, Prestel, Munich, 1995.

- Guy Conde-Reis, “Paul Hankar en de invloed van de Chinese architectuur”, Erfgoed Brussel, 19-20, 2016, pp. 93-105.

- Lieven Daenens, “Bouwkunst als synthese van verschillende uitdrukkingsmiddelen”, in: Werner Adriaenssens, Lieven Daenens and François Loyer, Paul Hankar als interieurarchitect, King Baudouin Foundation, Brussels, 2005.

- Kazuko Koizumi, Traditional Japanese Furniture. A Definitive Guide, Kadansha Intern, Tokyo/ New York, 1986.

- François Loyer, Paul Hankar. La naissance de l’art nouveau, AAM, Brussels, 1986.